Carole Roberts

In the recent history of Australian art, there are some names which have not been given the attention warranted by the importance of their practice. These artists largely came out of Sydney College of the Arts in the early eighties, and from around 1984 they began to work in the context of French post-structuralist theory.1 It must be emphasized that they never formed a "group" as such, but, in common, their art worked with the theories of Baudrillard, Deleuze, Derrida and Lacan, which questioned the whole notion of "communication" in terms of concepts of the independent operation and function of language.

Such ideas seriously undermined presuppositions in both the aesthetics of modernism and also in major political and psychological critiques which had acted as the alternative to modernist formalism. The old dialectic was severely pruned back to even more basic questions concerning the relationship of visual art to both its referents in "reality" (including psychological and political "realities") and to its addressee in the viewer. Post-structuralist analyses of this relationship ranged from the outright nihilism of Baudrillard regarding simulacrum and referent to Deleuze's attempts to subvert hierarchies of subject-object relations in favour of more fluid planarities. There was also the psychological-linguistic determination of self and other which in different ways, Lacan and, far more rigorously, Derrida investigated.

Such concepts were given airing at the highly influential Futur*fall conference at the University of Sydney in 1983 as a result of their sponsorship by certain members of staff at the Power Institute with whom the artists under discussion had contact.2

The significance of the emergence of such interests among Sydney artists has not been sufficiently documented nor analyzed since they have largely been overshadowed by a slightly older generation of artists promoted as the official face of the Australian avant-garde overseas. In examining the bibliographies of the younger artists, one finds that, certainly, the theoretically oriented journals such as Art & Text and On the Beach took some note of their work. But, overall, some thorough re-assessment of the influence of post-structuralism on art in Sydney in the early eighties is necessary.

Perhaps it is the austerely subtracted quality of such work (although still, in the main, within the tradition of canvas and paint) which initially deterred any approach to it. Such cowardice is hardly to be condoned in view of the paradoxical situation that it did not take long for the superficial look of these art-objects to be emulated as a "style". But this does not necessarily suggest that entry into the discourse of the Sydney work at a more rigorous level is difficult. In fact, the polemic of the work is very direct and forceful. Perhaps this is another reason why it has been neglected. Critics find it hard to answer direct questions. Beating around the bush makes far more stylish writing.

It must be stressed from the outset that, in Carole Roberts' case, the minimalist "Look" is only an appropriated language and not the whole point of the work. She took on a particular intellectual stance questioning the possibility of communication between viewer and artobject. However, Carole Roberts organized this relationship in a series of very plain and immediate presentations which directed the issue along highly specific channels. This has not been adequately recognized. Instead, the tendency is to focus on the "minimalist" and "conceptualist" appearance of her work which at this historical moment is, surely, hardly an issue any more.

Carole Roberts' intention is to slip through the customary rhetoric of the surface, to turn it back against itself and question on what basis such a surface, whether illusory or abstract, is able to communicate. Or, more importantly, if it is possible for communication to take place at all. Roberts asks on what grounds has it been assumed that an inter-relationship between viewer and work ever existed? In short, what constitutes an art-work (specifically a painting) at its most fundamental point of engagement with the viewer.

Roberts tackles this minimalized discursivity via minimal visual means: such as a resistance to the seduction of canvas and paint; minimalism of form and surface; lack of finish or, conversely, such a high degree of finish that the surface becomes almost (though, significantly, not totally) impersonal. In addition, in her reaction to the expressionism of the early eighties, Roberts turned to the objectivity of architecture and space, devoid of all human presence and the emotionality of brushstroke. The work at the first Future Unperfect Show at Artspace in 1984, and at the Traces of the Object at the Mori gallery in 1984, were an outright rejection of the expressionist canvas with its auras of both art-object and significant humanism. And her interest in the relationship of the art work to its architectural situation was especially evident in Open Plan, exhibited at Traces of the Object, which comprised of a ground-plan of the Mori gallery.

Through such devices Roberts asked how communication was really possible from work to viewer outside of aesthetic conventions. When the traditional signs are removed, what is left in that inter-actional space? How is it that painting is?3 At this period, she was expressing more of a doubt that it really was at all and that the painting probably communicated, and had communicated, very little. Her discourse was to become more complicated from this point.

THE CLEAVING

Roberts went on to tackle such issues more incisively in a series of works entitled The Cleaving. Created in 1985 this series was exhibited at the Mori Gallery in 1986. The Cleaving consisted of twenty small works. For each of these works Roberts used a flax canvas as the initial support, this was painted white. She mounted a canvas board over the middle section of this canvas leaving a top and bottom section exposed. A fluid black pattern was painted onto the white surface of the canvas board. Another, smaller, canvas board was attached to the first canvas board. This was painted black and varied in position according to the work. Sometimes it was in the centre, sometimes to either side of the centre.

The Cleaving was reviewed by Pamela Hansford for Art Network but, unfortunately, the magazine folded before the review could be published. Hansford spoke of the black rectangles functioning not as metaphors for nihilistic emptiness but "like psychological brakes to stop the viewer absorbing the work in a simple act of cash and carry viewing. Sight's easy voyeurism is put in check and the viewer is asked to find a way to see."

The viewer's expectations of such surfaces were frustrated. There was no fulfillment. No "insight" into some psychological illumination promised by the code of marks. Instead the viewer was conceived as "cleaving element between object and space". In particular, the viewer's perspective was seen as a cleaving element with regard to the painting's perspective. The perspective of the viewer cleaves that of the painting. It does not “realise" the work, nor bring it to completion, nor to fruition, as in the Renaissance tradition of perspective in which the exact positioning of the viewer made sense out of the geometrical skeleton on which the painterly illusion was based.

BUREN AND DECOR

Paradoxically, although this cleaving initially may be seen as an "intrusion" into the integrity of the work, the net result of the interchange is that the viewer becomes aware of the totality of the situation of the viewing. Carole Roberts' Decor installation at the Bellas gallery, in 1987, engaged the polemic of Daniel Buren as an extension of her interest in the situational aspect of viewing. Buren, of course, is also particularly concerned with the situational aspect.

For Roberts, Buren was to provide a textual site from which she could continue to alert the viewer to the preconditions operative on what was assumed to be an "innocent" procedure of "dialogue" with a painting. More than most artists, Buren had queried this seeming "openness" and immediate accessibility of art's "communication". Going below the surface constituents, as traditionally ascribed , he questioned the fundamental construction of the work of art. Buren has said of his work:

The work in progress has the ambition not of fitting in more or less adequately with the game, nor even of contradicting it, but of abolishing its rules by playing with them, and playing another game, on another or the same ground, as a dissident.4

Buren transferred into a three-dimensional siting, into the vulnerability of a total environment, the two-dimensional painting which had hitherto been rendered inaccessible to pragmatic critique by those traditional discrete parameters which had demarcated it, in the European tradition, as a ·particular type of metaphysical "sign". That is, the siting of the painting within the conventions of frame, or canvas support, had served to locate it immediately within an inviolable, accepted code. This had guaranteed to it the triggering-off of a whole range of stereotyped signification which, by no means, had any actuality. As in the case of any "script", painting, by reason of its material presentation, was able to rely on the conventionalized credibility of its surface to hide the fact that little or nothing might be being transmitted to the viewer. The cultural assumption, unless the situation is indicated to the viewer or reader, is that an “authorized" presentation is a warrantor both of conceptual value, as well as of missive coherence.

Buren's approach was direct. He avoided the signification of "artness" by the simplest and now, in hindsight, most obvious, procedure of refusing to use either frames or traditional supports. He painted his stripes directly onto the walls. Alternatively, he has displayed them out in the open as if they were flags. As soon as the conventional, supportive parameters were removed and the work was confronted with its environment, it was clearly perceivable that both the form and content of traditional painting could be remarkably thin and superficial.

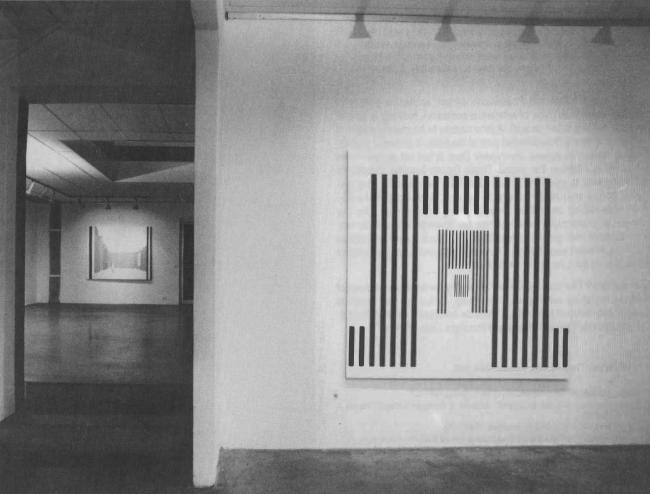

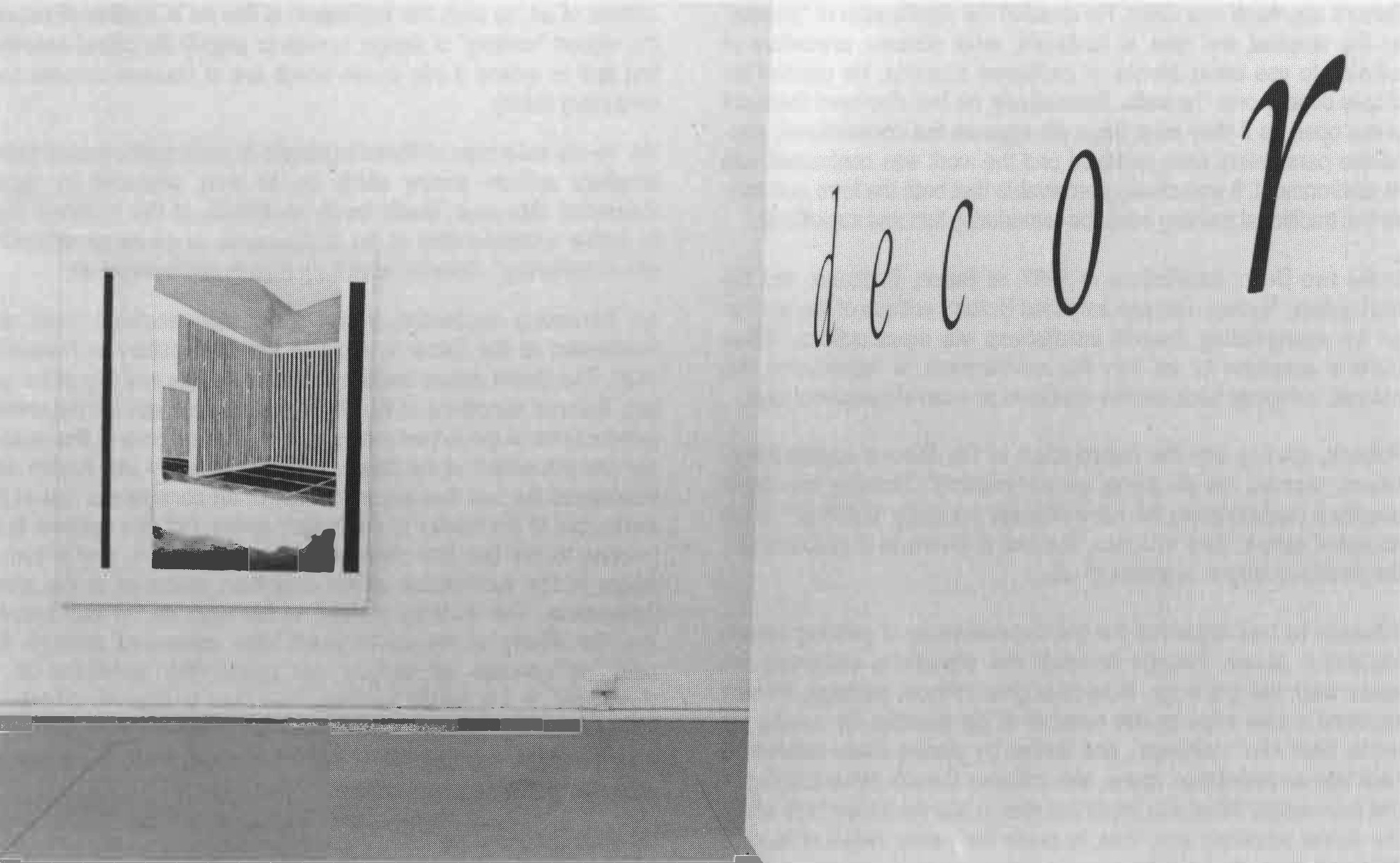

In the two Decor installations of 1987, at Bellas, Brisbane, and the Mori gallery, Sydney, Roberts amplified Buren's critique of the work of art by appropriating Buren's installations via reproductions. When Buren's extrusion of art into the environment is reproduced, his polemic collapses back into the condition of a two-dimensional sign.

Roberts, starting with the reproduction of the Buren's spatial installations, recodes his situational art as "painting". Thereby, her works acquire a paradoxicality, for her works are not really "paintings" in the accepted sense. Their intention, like that of Buren, is to problematize the traditional notion of a work of art.

Whereas he had expanded the two-dimensionality of painting into an installation space, Roberts reversed the procedure, collapsing his works back into paintings. Buren's original critique, perhaps, thereby acquired a new edge by the reversal of his polemic. By turning his works back into "paintings", and further by placing these references back into an installation space, she critiques Buren's more avant-gardist subversion. What was important was to site the space from which the viewer perceives and, then, to make the viewer aware of its conflicts and conceptual dangers.

One could say that Roberts simultaneously uses and redirects Buren's "dissidence", both against the same uncritical superficial acceptance of the tradition of the constitution of an art-work, but, further, against Buren himself, thus questioning whether Buren had taken his own critique to its fullest extent (to the extent where the critique even turns on itself). In the Decor show, she implicated Buren's stripes with interior decoration, this could, at first, be seen as a denial of his critiartness of art, as such this implication of fine art in another discourse, the related "territory" of design, serves to amplify his critical examination and to extend it into issues which are of concern to more contemporary theory.

Her re-use/extension of Buren's polemic is more sophisticated than a simplistic anti-art stance which on its own, unguided by tighter theoretical discourse, would hardly contribute, at this historical date, to further understanding of the problematics of art as an ostensible site of "meaning". Roberts' work both rejects and accepts art.

An increasing implication in the installation aesthetic itself was manifested at the Decor II show at the Mori gallery in November 1987. The Buren stripes became reflections of the real site of the gallery. Roberts' renditions of the Buren installations echoed the shifting perspectives of the actual rooms in Mori, the lowness of the ceilings and the placement of the doors. The play of reality and illusion acknowledged the fact that any exhibition of art consists not just of the works, but of the totality of the gallery space. Roberts seemed to be pointing to the fact that often, at such an exhibition, one is just as aware of the architecture of the exhibition space as of the works themselves. The "missing content" of her work on the wall intruded into the totality of the environment. She uncovered, through this reflecting process of surface on space, the ambiguity of all viewpoints. In her hands paintings lose their traditional authority as supports of reality, that is, as signs of a hegemonic gaze which determines the only possible viewpoint, instead all possible views are shown as paradoxical, as fallible.

On what ground does validation stand when space itself is a determined cultural construct, pre-coded into a sign system, reducible to surface, to a thin veil , mockingly rarefied, itself available to exhibition, to display, to survey. No longer the privileged site; privileged by materiality to the possession of an objectivity which alone empowers the ability to determine subjective and objective, valid and invalid, and, thereby, the very possibility of meaning itself. The ambiguous viewpoint of the Decor works cleaves the ."objective space" of painting. Losing substance, the work of art becomes an interface, at this interface occur confluences and assemblages, incessant recombinations rather than stable unity.

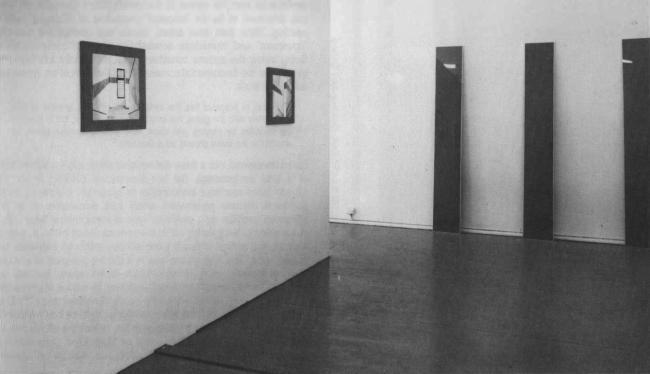

Graham Coulter-Smith

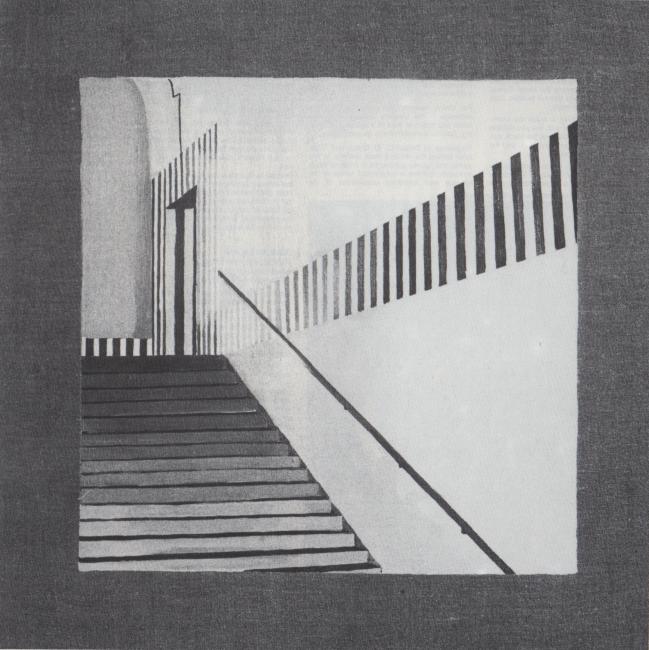

Roberts' latest exhibition at Bellas (July 1988) is a continuation of her dialogue with Buren. It consists of small "paintings” which show reproductions of reproductions of Buren. The reproductions were views of a staircase in a nineteenth century chateaux on the walls of which Buren painted his stripes. The reference to Buren immediately places doubt upon the status of these little "paintings” as paintings, as works of art. This doubt is increased by the fact that Roberts has placed three long grey "stripes", framed (in aluminium) and covered with perspex to the side of her "paintings". These seem to parody the "paintings" in the way in which their neutral grey emptiness is so carefully framed and covered in perspex. The long grey works further their parody of the paintings hanging on the wall in that they are left leaning against the side wall as if in a store room.

In this latest exhibition Roberts continues her dialogue between art and antiart. We begin to realise that the little "paintings" are as empty and casual as the three grey strips. Even the "frames" of the little paintings are rather fake in the sense that they simply consist of a couple of inches of masked-off blank canvas.

Buren critiques the "work of art" by exhibiting non-paintings, hangings or inscriptions on the wall, which have none of the traditional support attributes of the work of art (frame and stretcher etc.). Roberts, via the magic of reproduction, goes on to reconstruct Buren's anti-painting in terms of a simulacrum of the "work of art". This reconstruction could be seen as mocking Buren's avant-gardist "dissidence" but it is just as much an elaboration of Buren in the sense that her simulacrum of the work of art is even more emptied out than Buren's non-paintings.

It is more empty because, unlike Buren, it accepts the subtle and surreptitious process of absorption - that curious way in which antiart always ends up as an aesthetic object. Buren, like many other "dissidents" tends to overlook this intriguing phenomenon. It is as if Buren is trying to say that there is something which lies outside the thinness of the aesthetic signifier: situational praxis for example. The simulacra of paintings offered by Roberts, on the other hand, suggest that there is no way out - that the situation can just as well become implicated in the thinness of the aesthetic signifier as the aesthetic signifier can be deconstructed by its synthesis with a physical situation.

At one level Roberts implodes Buren's critique of the work of art. But at another she expands it, in that she avoids the binarism of art versus antiart. By accepting the phenomenon of absorption she engages in a process of play which is more radical than historical avant-gardist antiart in that it uses the power of contemporary theory to explore the interrelationship between art and life.

By accepting and playing with the process of absorption, Roberts begins to show the play of implication between art and environment. On the one hand art's implication in tts own absorption into commodity culture (decor); and on the other hand, tts status as a paradigm for emptiness, for the labyrinth of semiosis which defines all cultural formations in terms of pattern making.

The involvement of art in everyday life becomes potent when the art work makes one realise the essentially arbitrary nature of all communication. In this manner Roberts' work, like postmodernism in general, points towards a massive cultural questioning.

Urszula Szulakowska would like to thank Graham Coulter-Smith for his willingness to debate the possible relationships between Carole Roberts and Daniel Buren

Decor II Installation Mori Gallery, 1987. Courtesy Mori Gallery.

Decor Installation Bellas Gallery, 1987. Courtesy Bellas Gallery.

Installation view, Bellas Gallery, July 1988. Photo: Richard Stringer. Courtesy Bellas Gallery.

Liminal Space (Spectrum), 1988. Oil on linen, 50.8 x 50.8 cm. Photo: Carl Warner. Courtesy Bellas Gallery.

- These artists would include those associated with the Future Unperfect exhibition: Janet Burchill, Kate Farrell, Lindy Lee, Jennrrer McCamley, Catherine Mills, as well as Carole Roberts.

- A selection of the Futur*fall conference papers has been published, see: Alan Cholodenko, Edward Colless et al (editors). Futur*fall: Excursions into Post-Modernity. Sydney: The Power Institute, University of Sydney, 1986.

- Paul Cameron, On the Beach 6., 1984, p. 46.

- Daniel Buren quoted in J-F Lyotard, 'Preliminary Notes on the Pragmatic of Works: Daniel Buren" in October 10, Fall 1979, pp. 59-68.