Beckett and Proust

Nicholas Zurbrugg

Colin Smythe/Barnes and Noble, Bucks. UK and NJ USA.

Between "habitual Boredom" and "non-habitual Suffering" swing the characters in Beckett's writings. They wait only for that sleepiness which indicates to them some temporary respite from their contradictory, slivered selves…"things seem fated to go from bad to worse, and then, with luck, to bad again"…1

Beckett's essay on Proust (1931) has served to misintroduce a number of generations of critics to Á la recherche de temps perdu. Nicholas Zurbrugg has turned around this classic essay so that Beckett's formidable depression concerning human relationships, art and self no longer subsumes Proust's analysis of discontinuous perceptions and modes of being. Rather, Beckett's wracked and misformed self is introduced into a new understanding of a dualism in Proust's system. For that modernist author discusses also positive modes of existence, as well as the negative, "inauthentic" modes of being which are the only ones acknowledged by Beckett and, after him, most other critics (specifically those looking for the sources of post-modernist, fragmented texts and characterisations).

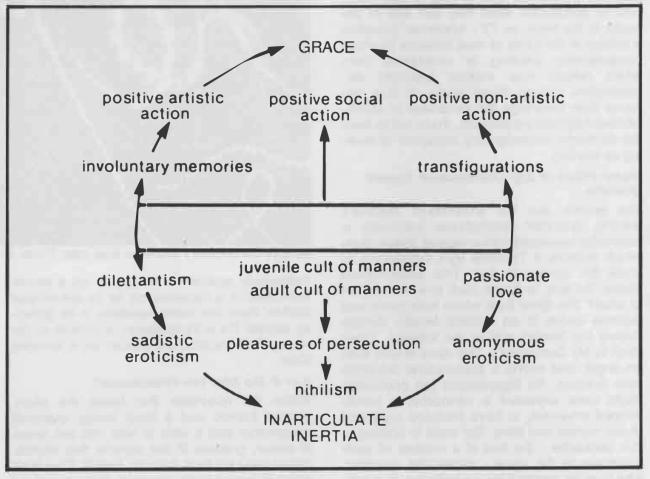

Although he consciously avoids a biographical approach (preferring to argue from within the texts), Zurbrugg has restored a view of Proust which revivifies the image of the ultra-cool, disenchanted dandy of Parisian society who once confessed himself to be lacking in all moral sense. Arguing for the defeatist silliness and inconsequence of such a statement, Zurbrugg has shown Proust's superlative concern to be that of self-realisation through ethical behaviour. Far from believing "art" to be the one and only justifiable activity and the only means of attaining self-understanding, Proust analysed the way also of selfless, discriminating, ordinary human behaviour. Zurbrugg shows how precisely and clear-sightedly Proust was able to cut through the fantasising imaginations of the ego which projects so many images onto the object of desire that communication and knowledge is blocked. Unless consciously rectified and fought against, such fantasy leads downwards through degenerated viciousness to total inert nihilistic non-being - which is where Beckett's characters helplessly sit or wander in circles. Far from lauding the imagination as the highest human faculty, Proust thinks that it must be controlled either by rigorous self-effacement or by the disciplines of artistic creativity, both of which release the involuntary memory which inspires to a more positive and communicative form of action and feeling.

Proust, in his own life, was noted for simplicity of heart. The great socialite was more than capable of taking some ancient maid-servant to an evening at the opera, or of standing in for a doorman when his wife was sick, or, as a grown man, of weeping when told a story about a schoolfriend so ashamed of a dowdy mother that he pretended she was the family servant. Proust certainly, from Zurbrugg's investigation, believed in personal responsibility.

Though demonstrating Beckett's wilful obtuseness at such points, Zurbrugg refuses to reject his essay in favour of a "resigned reference to the way in which this Irish scallywag's critical practice is no better and no worse, than it should be".2 The essay is used to reveal Beckett's critical manoeuvres and his own artistic investigation of the broken self.

Zurbrugg tracks Beckett with respect and affection from his earliest period when Proust's notions of the sparks of intuitive inspiration still registered true with Beckett, through to the middle period of his clogged and monologued speakers, as in a particularly acute and fresh reassessment of Watt when Beckett with easy, disengaged savagery presented ... "the power of the text to claw".3 From "the peculiarly unnerving impact of Beckett's most horrific writing"4, Zurbrugg moves to an analysis of his later works, which, while (thankfully) refusing to concede an inch to any kind of mystical positivism and retaining the honest disbelief in self, art and life (and above all, communication), begin to recognise a kindred spirit in the negative enlightenment of the "dark night of the soul" theologians, such as John of the Cross and Meister Eckhart. Across death humanity will continue to grump in a timeless condition of disenchanted, painful but honest and, therefore, truthful, oddly secure, relativity. This is no small discovery of Beckett's, as Zurbrugg rightly emphasises. Really, what has "art" to do with any of it? Delight, for Beckett, is only the brief grace of witnessing the moment of extinction.

For to know nothing, not to want to know anything likewise, but to be beyond knowing anything, to know you are beyond knowing anything, that is when peace enters in, to the soul of the incurious seeker.5

Or the sad little dream of the Unnamable:

if only I could put myself in a room, that would be the end of the wordy-gurdy ... doorless, windowless, nothing but

the four surfaces, the six surfaces, if I could shut myself up, it would be mine, it could be black dark, I could be motionless and fixed.6

Zurbrugg reveals both these key-figures of the modernist and post-modernist trends as concerned not with form and style, but with ethics on their own terms.

His analysis is a fascinating piece of detection, revealing the turns and elisions of Beckett's thought as he avoids, or swings over to his point of view, Proust's psychology, or, conversely, hammers home a startling elucidation of Proust's own sense.

Considered as literary criticism, this eccentric essay is a strange mixture of the productive and the reductive, and of the enthralling and the appalling ... In a nutshell, the virtues and vices of the essay are equally spectacular.7

Pointing out the reductive aspects of a structuralist analysis of texts, Zurbrugg's approach is more eclectic, combining traditional methods of exegesis with appropriate and inventive use of concepts from Barthes and Baudrillard, extending their ideas from a visual to a textual context which works well in the critique of Beckett. His forte, however, is in the close comparison between Beckett's and Proust's texts and, especially, Beckett's ungracious misuse of his former master's most moving and most effective insights, converted to an outrageous, parodic misinterpretation (as also happens in Beckett's re-use of the Anglo-Irish modernists, such as Joyce.)

For example, Beckett converts Marcel's memories of his tapping on the wall of his bedroom as a child to his grandmother, who would tap back.

This perfect early morning moment which began like a symphony with the rhythmical tapping of my three taps to which the partition ... replied with three other taps ... in which it somehow transported the entirety of my grandmother's soul ...

This becomes in Molloy's communication with his aged mother far from a dialogue of sound "knocking her on the skull" and then "replacing the four knocks of my index knuckle by one or more ... thumps of the fist ... ".8

Zurbrugg's book has many amusing insights - often, necessarily, of the above grim character. It is an original and important contribution to the study of the origins of post-modernism.