Hiram To

Drained (compulsive surveillance)

There is no such thing as neutral surface. No matter how "decontextualized" an image may be, or however bland its form, or, the converse, no matter how much the visual data is impacted so that a cross-cancellation of codes produces a blank emptiness, nonetheless, the viewing mind will automatically recontextualize visual information which is presented to it.

Post-modernism of the early eighties asserted the possibility, indeed, the inevitability, of neutrality - a continuation of the aesthetic of indifference of the sixties. However, recently there is a re-acknowledgement that all information has its locations, that "decoding" is simply not feasible. Different explorations are being undertaken into the construction of the visual narrative of an image.

From the evidence of his latest installation, Hiram To appears to be engaged in such an analysis. The surface manner is minimalist. Minimalism has lately undergone a resuscitation on the international scene, but, as a term, it needs careful definition since its use over the years has grown too wide and includes (apparently) colour-field. It is clearer to speak of "reduction" as very specifically directed. A given aggregate of various forms and visual modes of expression is pulled apart and certain instances isolated and refined. In the present case, coloured photographs froze moments from an installation which Hiram had made recently at the Hong Kong Fringe. A video of the installation formed part of a television interview with the artist.

This initiated the spinning of a very fine web of new associations which were stated in such a reduced manner that the interstices of the open web became as important as the imagery itself - spaces for the play of time.

The installation could not, properly speaking, be interpreted as a series of layers of personal and impersonal history and experience, as well as of active criticism of the artistic and cultural milieu of Hong Kong, or Brisbane, or anywhere. The work did not organize itself as this type of systematic hierarchy, but rather, threads of such different connotations were looped across each other horizontally in the temporal element. For, this work connected essentially with Hiram's earlier installation at John Mills, Irrelevance, as well as with his second performance there, Decisively Oxstralyan, at the April performance season, and it foresaw future work. Thus, it should be considered as a journal, a progressive work to be accomplished (presumably) in infinity, each sequence containing a lacuna, something more to be said, within it. There was also a deliberate spatio-temporal relationship between the artist's work in Brisbane and in Hong Kong (which included an attempt to produce simultaneous performances in those two places with the help of Adam Boyd.) This was a model of the subjective nature of time, everywhere at counter-point to everywhere else, and yet, the random actions within it repeating, curiously identical, synchronically.

The whole installation was, literally, embedded in a narrative text concerning the rubber cement produced by the Union Rubber Company (which is a standard part of the designer's toolkit). The image of the cement-can resurfaced an earlier concern of the artist in Irrelevance, namely, the relationship of "design" to "art", that is, of "idea" as marketed commercially, and "idea" as loaded with transcendental aesthetics, uncontaminated by economic factors. Was the distinction valid?

The commercial success story of the cement was related to the artist's personal experience of it as a designer: his allergy to it. A can of cement took-up the centre-space of the room on an old three-tiered dressing-table, constructed in the form of a set of steps. Gladioli were set around it in reference to another personal connection with Hong Kong. A long piece of undyed calico was draped over the cupboard in the manner of a shop-window display, but also recalling strongly, with the flowers, funeral parlours and, also, Chinese mourning clothes.

Thus, at every point of contact of each element with the next, a new narrative spun off: points of intensity within a multiplicity.

This billiard-ball way of producing intricate associations of place, time and person was relocated along the walls of the gallery as significant points which were lifted out and reduced to varying surfaces, but still maintained their locus in the centre of the room.

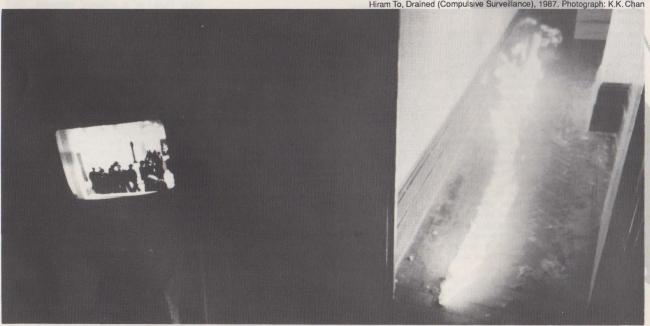

The stepped dressing-table reflected a set of stairs made of bamboo and paper (like Chinese funeral accoutrements) which the artist had used in the Hong Kong installation. Here, they had been arranged to partially block the entrance to a small room off a narrow corridor which had contained some of the two-dimensional plaques now in John Mills. The end of that corridor displayed a relief of flowers. Cement had been poured down the centre of the corridor and set alight. A TV to the left of the corridor played Legal Eagles, a Robert Redford film involving a fire-disaster. The Hong Kong performance had been videoed and in the John Mills installation the video was played back on a monitor standing on the dressing-table. The video finally focused on an image by Edward Ruscha of the LA County Museum of Art on fire.

Stills from the video of the performance and from photographs of the installation were arranged along the wall, punctuated by a record of "Learn to Speak Chinese". One set of photographs showed a large mirror covered with water on which floated the record and above it hung streamers of video tape. Thus, the installation kept itemising objects as recorded information which was elsewhere in the past and in space, but which kept re-appearing as real things in the new location: spirals which emerged out of the electronic media and disappeared back into it, real and unreal, memory and actuality ... memory as what sort of truth? Cross-reflections modified by time.

Across a back-wall, scenes from Hong Kong, especially shop-windows, were printed onto Ikea crockery, which is usually used as touristware. The right-hand wall returned to the photographic surface: a new series intended to act as moving installations, non-photographs, of the sub-street entrance to the New Hong Kong Bank and of artist John Young in front of installations of Sidney Nolan paintings in Exchange Square. A sequence of textured surfaces followed (those which had hung in Hong Kong), including designer's gradation paper. The door interrupted the series, enshrining another record on its surface, so that a formal play of geometrical shapes resulted, in which the wooden boxes framing the crockery played an ironic role.

Perhaps we have become too accustomed to a pile-up of narratives and, maybe, it is time to return to a more economic use of image in order to comprehend such visual structures, instead of plundering and misusing them in the manner of some post-modern art-forms. Instead of dense textural catharsis, it can be equally effective to work in the reverse direction, as the installation above has demonstrated: its sparing references still permitting a most complex inter-relationship of themes.