Virginia Barratt

The lethal stage

For her first major solo, the Director of John Mills, Virginia Barratt, produced not just one, but two performances, which grew over the space of a week from a two-act situation into a three-act completion. Injuring herself too badly to continue the first time (after cutting herself with the axe which she was wielding, something which the audience half-expected consequent on the tension which the act had built-up), the repeat had grown from being a head-on collision with the malignant sources of personal conditioning into something of a resolution, albeit quizzical and suspicious, in a new third act which paid wry and questioning homage to those factors.

Within her detached analysis, Virginia displayed the bitterness at the heart of all the Romantic myths of completion and totality. For, they not only insidiously distorted reality through their mist of rose-pink, but they were the very cause of grief, in place of their promise of hope and beauty. The basic theme of the Triptych was the question of real substance in these myths. It seemed, in this performance, that some residue of worth was left in them after all the purging of self from their influence. Amidst the irony, arose a heroism. The impression of the heroic was the chief one in the performance. Virginia deconstructed the Romance, but left a metaphor in its place of the continuing quest for the integration of personality.

The sense of a deep affection for some aspects of the Romantic underlay her performance. Within the pain of the deception of the encounter with enchantment, within the spell-that-could-not-be-broken, the sleeper could find her own goal on her own terms. The roses, the love-stories, the candles, the dreams, the storms, the seas and their corals and bewitched sirens were worth pursuing for the sake of their own ambiguous and dangerous beauty.

It would be very misleading to classify Virginia Barratt’s performance in the category of "feminist” performance of the seventies type. This had explored the magical realm of "woman” created by the patriarchy as inverted mirror to itself. In the eighties, such an exploration is probably no longer possible in quite such clear-cut terms. For some privileged intellectual sections of society, at least, the problem now is less than of female versus male image, than of the very existence of the autonomous individual at all. Virginia’s performance was one of these coolly analytical dissections of self, but one which, as is the case in other post-modernist discourse, was no longer afraid to drop the pose of empirical detachment in order to acknowledge wryly the continuing power of the area of analysis over the analyst, a wistful hope that the Ideal could still (somehow) be realised within the realm of Nature. The problem of the Romantic seems to have become less a question of how to exterminate it, than of how to re-negotiate it by turning its static and fixed conventions into new images which would be fluid and transformatory enough for the transcient and evanescent postindustrial state of mind. We are still in quest of a set of living symbols (or signs at least) without which no culture can hope to stay alive, since it must have a mirror in which to view its own progress or regression (within its own terms).

Virginia constructed the Tantrum Dance at the beginning of her performance as a loose, but firmly committed piece of choreography, which displayed her increasing confidence over the course of the year in her movement studies.

(She had already shown this new determination and energy in a sophisticated performance at the Eyeline launch in May.) The theme of the Tantrum Dance was the vampirism exercised over the innocent self by forces which were inner, but imposed from the outside. Virginia’s own voice-over read a set of dictionary definitions of words implying force and energy. As a sleeper, she stirred slowly on the floor under their increasingly jarring impact. Eugene Carchesio discretely played ambient, minimal variations on the saxophone which maintained a re-assuring lyricism behind the increasing tension of the word-action relationship.

Once awake, the protagonist found herself firmly in the grip of the energy which had entered her dreams. Like Mephistopheles, it had promised power, but in reality, the victim found a destruction which was directed against her own self. Seizing the golden axe, the archaic Minoan symbol of both monarchy and death, the dance turned into a series of whirls and maddened propulsions which were generated centrifugally from a kinetic element of such weight. It culminated in the destruction of a fragile, sacred enclosure, a "temenos" which enshrined all that the performer had found most personally significant, chiefly the sea and its hidden grottoes of minute, deeply coloured and radiant life-forms.

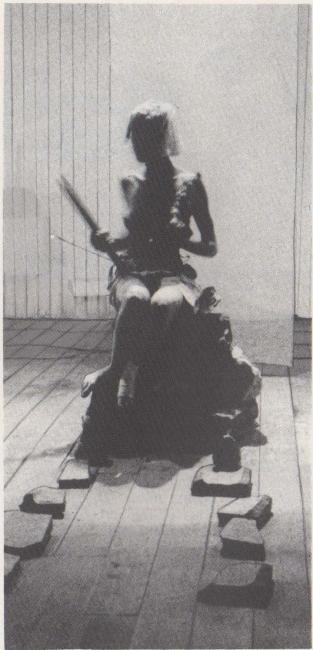

The second act began with a swimming sequence: the actions reflected a soothing voiceover. It echoed the first sleep, but was now a regeneration which represented a return to personal values, specifically to those of kinesis, free from the conditioning of the verbal. It was also a more universal image of restoration through a return to the primeval water-origins of the whole species. Virginia then built a monument out of rocks, piece by piece, trundling them slowly and painfully across the floor. It replaced the fragile butterfly-wings of the original enclosure which could not survive the forceful changes of the psyche which had constructed it. The new sacred site was located firmly in the earth and the sea. The performer, thereby, asserted herself as sole authority against the determinants of her past. She seated herself on the rocks with the insignia of power, an image which still recalled the fragility of the little mermaid of Hans Christian Andersen, as well as the seductiveness of Greek sirens and the absolute assurance of the Empress of the Tarot pack. Negative and positive were peacefully reconciled.

In the last act, there was a final engagement with personal sources of conflict arising from the influence of the fairy-story and the lovemyth. The rocks were crowned with white porcelain roses from a grave, accompanied by a pile of books, representing such pernicious and, yet, seductive texts, and by a lit candle, another Romantic symbol. Reading a collage of all the most ambiguous moments in the stories of Hans Christian Andersen, Eloise and Abelard and from a child's book of ballet stories (Giselle on the "lethal stage" the very epitome of the sacrifice claimed in return for Romantic love), Virginia caused the rocks, candle and pile of books to collapse, signifying the crumbling of the structure of the stories… but not, paradoxically, their innate compulsive attraction.

“Death is a great price to pay for a red rose…”